"I Feel Like He's Every True Comic's Soul"

An interview with Joshua Edelman, director of Al Lubel doc Mentally Al.

Est. Read Time: 29 minutes. Read Time brought to you once again by the Ashburton Energy + Hair Logistics Group, in association with the Bradley Hills Bureau of Corrections.

If you like the Sternal Journal, forward it to a friend. They can find the Best of 2020 list here.

Hello Sternal Journalists!

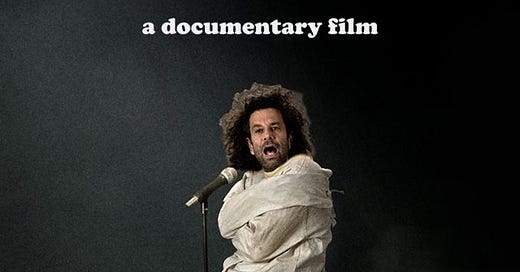

It’s the end of the month, and you know what that means: time for another Sternal Journal interview! This week, I had the true pleasure of chatting with Joshua Edelman, the director of Mentally Al, a documentary about legendary-yet-relatively-unknown alternative comedian, Al Lubel.

I love this movie. You may already know that because I accidentally have recommended it twice in prior Sternal Journals, but I also have now watched it twice, so doesn’t actually count as a repeat.

I first learned about Al when I was doing an attic bar show in London two years ago, and the host announced that there was a very special visitor from the United States (I was like, “They think I’m special?!”), and then they went on to say that this person had been on Carson, Leno, Letterman, and won StarSearch.

My most immediate reaction was “Okay, so they aren’t talking about me,” but my second-most immediate reaction was “Hang on, someone who was on fucking Johnny Carson and won Star Search is doing this attic bar show? In London?” As I learned from the film and my conversation with Josh, this atypical interaction is a hyper-typical introduction to Al Lubel.

When they see or know Al, people love Al. And not just weirdo nobody comedians like me, but rather weirdo somebody comedians as well. Look at this:

That’s Judd Apatow telling you to watch this movie. He’s even interviewed in it for a bit, as well as Sarah Silverman, who also tweeted about how great the movie is.

But, Sternal Journalists, don’t get all caught up in the starfuckery. This is not a great documentary because Judd Apatow and Sarah Silverman sat for interviews.

Rather, this is a great documentary because of reasons including but not limited to:

Al Lubel is a phenomenal, singular comedian and worth knowing about

You get to see, by my count, almost 20 minutes of real performance interspersed throughout the otherwise compelling story

There’s an incredibly fascinating, tragic, and funny arc about Al’s relationship with his mom that will make you pause and reconsider your identity as a child (even if that’s something you already pause and reconsider regularly)

It’s the most honest look at the life and psyche of a comedian I’ve ever seen portrayed in any medium ever.

We find ways to tie in Free Solo, Awakenings, and of course, The Last Temptation of Christ

The donkey story

The fact that Josh discovered Al by accident at a Boca comedy club when he (Josh) was 15, and thought Al was so funny that over a decade later, he’s spent five years finishing a documentary dedicated to celebrating and amplifying this person he believes the world deserves to see more of. Imagine the comedian, poet, writer you think deserves to be known by way more people. What did you do about it, like text three people? On top of being a brilliant film, this is some next-level signal-boosting.

And so I hope you’ll drop everything right now and watch the movie (available to rent for the low, low price of $4.99). But if you’re at work or pooping or both—a situation where you can’t watch a feature-length documentary right now—read the interview with filmmaker, comedian, and friend Josh Edelman now (and give Mentally Al a watch tonight!)

JS: When we first talked briefly over Instagram, you said you were always nervous about how the mom stuff played. I wanna hear about why.

JE: So the response to the film has kind of blown my mind. I didn't quite expect the resounding positivity. And a huge part of that has to do with the fact that I spent five years making it. You lose touch.

But for me, [the part where he visits his mom in the nursing home] is just the heavy part of the movie. I was worried that people were gonna be like, "It was fun before, but now it's too depressing. Why did I watch a movie about this guy? Why can't he just get over his mom and get his life together?"

But at the same time, I tried multiple times to shorten that section, lighten it up. And I was like, "Nah, I feel very strongly that everything that's in this part needs to be here."

And then interestingly enough, since the film's been out, that's been the part that most people tell me is their favorite, the part that hits the hardest. I had one person tell me that the movie made them rethink how they wanna raise their kid because they're a new mother.

JS: I mean, the sort of premise of the movie is "There’s this guy who the kingmakers of the comedy world think should be famous, but he's not." And that's a fascinating thing. But his relationship with his mom really is the emotional core of it.

He’s literally driving [to her nursing home] while telling you, "This is how this woman has ruined my life." And he's got the past as a lawyer, so he's making that case to his cousin who's defending his mom.

JE: I appreciate you saying that because at one point, the heading for that—instead of just "Visiting Ida”—it was gonna be called "The Trial of Ida Lubel." Because Al's a lawyer also, so to me, it sort of is like he's brought her to court for ruining his life.

With the whole movie, I tried really hard to step back and not pass any judgment on anything, and just let people take from any of it what they will.

JS: I watched the interview you both did with the Lower East Side Film Festival, and I appreciated that when Al said something like "Josh paints me in a really positive light,” you said, "I don't actually think it paints you in a positive light. I didn't intentionally paint you in a negative light, but I do want to make clear that other people don't necessarily watch this and think 'I want to have his life.'"

JE: [Laughs] I was making a joke the other day: "A lot of people have told me the film is depressing, but a lot of comedians have found the film inspiring. Many have told me that it inspired them to give up on their dreams."

JS: [Laughs]

JE: But there was a threefold thing I was really trying to do with the film. One: open up the world's eyes to this person who, in my opinion, is one of the geniuses and innovators of stand-up comedy, and does something that I still feel to this day I've never seen anyone do on stage.

And another thing I'm trying to do is a character study of a comedian. Who is he actually, who are we as people looking at him?

And then a third thing I really wanted to do was kind of just show what being a comedian is like. With all of the stand up clips, something I really tried to do was show Al doing multiple different types of comedy.

I feel like every clip presents a different aspect of stand up. You see him doing the singing thing, his name stuff, very avant-garde comedy.

You see him performing in front of an audience of like 1,000 people and the next day performing for four people in a restaurant.

You get to see Al doing crowdwork with people. You get to see Al doing very standard Seinfeldian comedy. In the mom section, you really get a good look at how he transforms his personal trauma into hilarious comedy.

And then in the donkey scene, you get a piece of how storytelling is built. You get two people telling the same story. One person is telling the story as a story, and then Al is transforming the story he tells into stand up, while also the whole thing is a deeper representation of who he is. He’s this fearful guy who actually walks on the edge of life, has lived life on the edge. And it terrifies him! [Laughs]

JS: It terrified him, but he also doesn't see it as that. It's a total paradox. He's living on the edge, it is terrifying, and he doesn't think he's doing any edge-walking at all.

JE: That moment where he's sitting with [his law school friend] Bob, they're in his nice house with his wife and his kids, and the pool and the dog, and Al's like living on someone's couch.

Here's two people who were best friends all the way dating back to when they were in law school. And to me, it's almost like The Last Temptation of Christ. Weird thing to compare it to. It just occurred to me now. But the movie's about how Jesus—right before he gets crucified—he envisions his life if he had chosen to lead it as a regular man, and have a wife and kids and all the pains and happinesses and joys and sorrows of being a regular person instead of sacrificing himself for everyone's sins.

And with Al, Bob's the look at the life Al could have had if he'd just chose to be the lawyer who got his life together and got married and had kids. Did divorce law for his whole life instead of going out to pursue this thing he always dreamed of being.

But I think it was worth it! I think he's great. I think the world is a better place for having Al Lubel's comedy in it, much more so than having Al Lubel's lawyering in it.

JS: [Laughs]

JE: Al views himself as terrified to live life, and Bob points out to him: "What do you mean?! You're the most daring person I know."

JS: Yeah. I do feel like the mom act is the emotional core of the movie, but the Bob stuff to me was such an important salve at the end. I have friends like Bob in my life. I have friends who are very successful, and maybe were artistic at some point, then went down the doctor-lawyer-consultant route.

And the tenderness when Bob is talking about he sees Al as a success, and that it doesn't actually matter what anyone else thinks—I think anyone on an artistic journey at least has some friends in their lives who say that to them.

But to be able to hear it come from this man who just told this donkey parable about Al, I was actually able to feel what my friends feel for me more than when they try to tell me themselves. It was such a perfect ending.

JE: You really feel Bob's love for Al. One thing again that I think is a really positive about the movie is you do really see how much love so many people have for Al.

Whether they're letting him live in their place for free, his mother, Judd Apatow and Sarah Silverman and Andy Kindler and Kevin Nealon being willing to take time out of their day.

Me! Spending five years of my life making a movie about this guy. I always say the weird happy ending of the movie is that it exists.

JS: Does Al feel that way? Does Al feel like it's a happy ending?

JE: So I had that show at the Improv [with Al], and he told a joke, which is he feels like Robert DeNiro in Awakenings, and I'm Robin Williams who pulled him out of his coma, and that he's gonna go back into it for sure.

JS: [Laughs] I actually saw him in London a couple years ago. Or we did a show together. A little bar show. And I had never heard of him before.

JE: Oh! Amazing! And was he brilliant?

JS: Yeah. I don't remember anyone else from that show.

JE: Most of the time, when I would tell people I made this documentary about this guy Al Lubel, they'd be like "Oh, I don't know him."

But every once in a while, somebody would be like, "Al Lubel? I saw him one time years ago. I thought he was the funniest person I'd seen in my life, and then I never heard of him again! But I always wondered what happened to that guy."

When you see him, you don't forget him. Love him or hate him, it stays with you.

JS: It actually reminds me of [rock climbing documentary] Free Solo. Somebody says something like "People who watch this and don't know anything about rock climbing are like 'Holy shit. What he's doing is insane.' But people who are serious climbers think it's even more insane."

And I think people who aren't comics will watch Mentally Al and think it's crazy, but seeing that he's like in an Atlantic City theater, and the day before, he's in the treehouse at [extremely indie comedy venue] the Clubhouse and I can tell that's the Gangbusters crab—and just seeing the crazy variety of shows that he's doing—it's even more insane to someone who knows the world. Does he feel like he can't say no to things?

JE: He does say no sometimes, and just imagine how shitty the offer has to be. But he almost doesn't say no.

JS: In the film, we don't necessarily see him write. Obviously watching someone sit down and write jokes isn't like cinematically appealing. But does he have a process? He talks about how he's so lazy and he doesn't do anything, so what does putting energy into writing look like for him?

JE: He goes on walks and thinks and just riffs on his bits, and records or writes them down. And then also, we'll be having a conversation, and he'll jot down jokes.

A bit that I thought was totally finished was the "You look homeless” bit. Just the other day, we were sitting down having lunch and I was saying "The main thing that makes you look homeless, Al, is your hair."

And he said, "Well, maybe I don't look homeless. I look barberless." [Laughs]

Somebody said something to me about finding your voice in comedy, and what finding your voice in comedy really is. And they're like, "If you got rid of all of your jokes, and all you had was yourself on stage, are you still funny and how does the funny come out of you?"

And with Al, who seems so written and articulate, when you talk to him, you start to realize his brain just operates in this structural joke form. He understands who he is so well and he understand his voice at this point so well that he speaks in his voice.

JS: You see in the scene where his roommate Gail says, "Oh, are we gonna go to that thing later?" And he's basically like, "It's a gig. I don't want you to come to a gig with me."

JE: It's an open mic.

JS: Oh, it was an open mic! Which is fully understandable. But he so quickly slips into basically riffing when he's like "Maybe that's what I should do. Be a reverse psychology comedian. I should be a comedian who says “Don't come to my shows.”

There’s a discomfort as she's continuing to try to have a conversation and you can tell he's just riffing. And any comedian has been in that situation or had someone accuse them of being like that.

JE: I look at Al, and I almost feel like he's every true comic's soul.

JS: [Laughs]

JE: He's all of our soul. If we just took out of us what our soul is and laid it bare in front of ourselves, it's Al. It's all the narcissism. It's all the anxiety. It's all the OCD. It's all the joke-structured thinking laid bare.

It's all of our biggest hopes and our darkest fears just right there in one person. Everything we'd be if we did fall apart.

JS: If you had seen him when you were 15 at the Boca Comedy Club, and then he just continued rising, do you think he would hold the same space as a comedian?

Because the space that he holds as a comedian is one thing. That's what he does on stage. And then there's the space that he holds as a kind of like a warning, but also a fun folktale.

Are they different? Would you be able to separate that? Would you still be obsessed with him in the same way that you are if he had had a generic rise.

JE: I think so. What I'll say again is I thought he was famous the first time I saw him and that I just hadn't heard about him.

JS: [Laughs] Right.

JE: I—no lie—have seen Al knock three people out of their chairs. The first person I saw him knock out of their chair was my best friend at the time who came to the show with me. He laughed so hard he fell off the chair he was on, and was still laughing so hard, he just started rolling side to side on the floor at the comedy club.

The next day, we went to school and the whole day, we were just doing his act for anyone who would listen to us. He was that funny.

So I think if he had really risen, if he didn't have the self-destructive tendencies to get in his own way and not wanna rise… I mean, he won StarSearch. He was on Carson, and he was on Letterman and Leno all these times. He won the Edinburgh FringeFest. He's accomplished all these things that nobody accomplishes.

JS: He just doesn't have money basically, and the jobs that give you money.

JE: I was thinking about this recently. Whenever you talk to someone and you're showing them a rough cut of something, and you're like, "It's a rough cut. Things are gonna change,” they go, "Yeahyeahyeah, I understand it's a rough cut. I get it. I won't judge those things."

After it's over, they're always like "Eh, it's not really there." And all the comments are all the things you just told them you're gonna change. They're unable to see the rough cut.

And I think Al wanted to constantly evolve as a comedian. But he wasn't famous, and he was playing these clubs, and the clubs knew he was this great guy, but he wanted to take risks and the risks didn't always go well.

So rather than the booker seeing, "Wow, here's this daring comedian who takes risks and is evolving as a comic," they just go, "Al's not funny. They didn't think he was funny. So Al's not funny."

JS: Before I let you go, I do wanna talk about your filmmaking. Obviously, so much of this is about Al, but I also really liked it as a documentary and as a film.

So—did you have a theory of documentary filmmaking that you were going into it with? Did you develop practices as you were going?

JE: In an ideal world, I wanted to shoot a 16 millimeter documentary, which is just an impossible thing to do these days without money that I was not gonna get.

So I knew that there was this camera called a Digital Bolex, which was a digital camera that shoots image sequences designed to feel like 16 millimeter film.

Because Al's a creature of the 90s. I wanted give the movie almost this 90s documentary feel. Crumb is one of my favorite documentaries ever and I wanted it to feel like stand up's Crumb.

So I had a friend who had a Digital Bolex and was also a talented photographer, who I invited on to be the DP of the movie.

So literally me and him went around filming, but we only had one camera. So I said, "Listen. Just constantly change the focal length. And I will figure it out in editing."

JS: [Laughs]

JE: I'm like, "Try to be smart about it. Don't be changing it in the middle of a sentence that seems like it's really important. But if something something seems like bullshit or if I'm asking a question, do it while I'm asking a question."

Every once in a while, I would have a very specific idea for something I wanted and I'd tell him to do that. There were a couple of shots that were designed, like Al walking up to the Borgata.

But otherwise, I mostly just said, "Keep the camera rolling. Turn it on, point it at Al, and just keep it going."

I had like seventy hours of footage when I was done with the main portion of shooting, then probably another twenty hours of footage in things I continued to shoot over time, and then also just all of the archival footage.

I spent a year editing it. Probably two years getting everything right in post production. And when I say a year, it was pretty much a year of me sitting down and editing it every day. It was a meditation for me. I didn't know how I was gonna put it together.

Editing it really felt like meditating on it, just watching the footage, putting sections together.

The first thing that I felt like I had the clearest idea of how to put together was Atlantic City. I felt like there was a story there of him going, bombing, doing well the second night after getting moved, and then jumping from being in the huge auditorium to the tiny room.

So I remember that being the first thing I put together because it seemed to make the most sense. And then I built out from there, and sort of kept asking myself, “What is this movie about? What are the themes? Who is Al?”

And then would put it together and edit and re-edit and watch.

JS: Were you ever like, "I just want this to be done!" Or you were really able to just be zen and say, "This will be done when it's done."

JE: So I would have a postcard I posted up on my wall that said, "As long as you do one edit today, you'll be one edit closer to finishing."

I have a joke where I go, "You know, I thought it was gonna take me four months to make this movie and it took me five years. I've talked to filmmakers a lot, and they always say things like 'My film is my baby.' And at a certain point, I stopped thinking of the movie as my baby, and started thinking of it as the adult man child I'm ready to move out of my house and stop costing me money.'"

JS: [Laughs]

JE: "I love you. But I don't want to see you again until you're making money on your own."

JS: I knew you first as a comedian. Here, you take the role of documentary filmmaker pretty much solely. But you also making it clear that you exist and you are a person. We see your parents and your childhood home [when Al stays with your family].

So I wondered how you made that decision to say, "I can show that I am a person because I'm talking about myself and being in my childhood home. But I'm not going to make clear that I am personally a comic.”

JE: I actually wasn't doing comedy at the time I made it. But when I was at my house, at first, I was apprehensive about letting my parents put him up.

Then I thought to myself, "You know. This movie's about Al. Al uses people. And now Al's using the documentary." So I guess I felt there was something poetic about it.

And then that section really becomes about how Al relies on everyone. Him talking about how he exudes a need for help, how people will unconsciously help him.

JS: You said before that, when you were 15 and first saw him, didn’t know Al wasn’t famous. Now, I'm wondering... is Al famous? It doesn't matter, but it's also so much of what the documentary is about. That that's the thing that's holding him back. The external lack of validation.

JE: I mean, I think the film has helped validate him in a certain way. He is getting more spots and attention at the moment. We've been hit up to get some bookings on the road. People know who he is. I'd say Al's more famous than people think he is, but less famous than famous.

I'll leave it on this story:

I took Al to breakfast at Café 101. I showed up early and I grabbed a table, and then Al walks in. Hair unkempt, baggy clothes, schlepping a huge bag, carrying a jug of water, limping in, and the waitstaff goes "Oh god, we gotta get rid of this homeless person."

So they go to get rid of him and I go, "Oh, sorry, he's with me." The waitress looked so upset. She just looked so upset that Al is with me. Every time she comes to our table, you can just sense how irritated she is that she's dealing with him.

And then at the end of the meal, a famous comic—she one hundred percent recognizes—walks over and goes "Al! How ya doin,’ man? It's so good to see you. What's going on? Give me a call sometime, let's talk."

And I looked at her face, and she’s like like, "What the fuck just happened? Who the fuck is this guy? This bizarre somebody that I have no idea who he is."

So yeah. That's like Al in a nutshell.

If you enjoyed Josh’s interview, check him out on socials @TheEdelmeister and on the old-style www internet at Joshedelmancomedy.com.

And if you made it this far, then of course it’s time for you to go watch Mentally Al.

And if you’ve already done that, then check out some of the other interviews we’ve done at the Sternal Journal with novelists, TikTokers, and screenwriters. And sure, hit that subscribe button if you haven’t already!

Finally, recommendations!

Recommendations

Al Lubel. Comedian.

Al Lubel. Comedian.

Al Lubel. Comedian.

Mentally Al. Film. (If you just watch, this bit will make sense.)

Until next week! Much love to all!

Julian